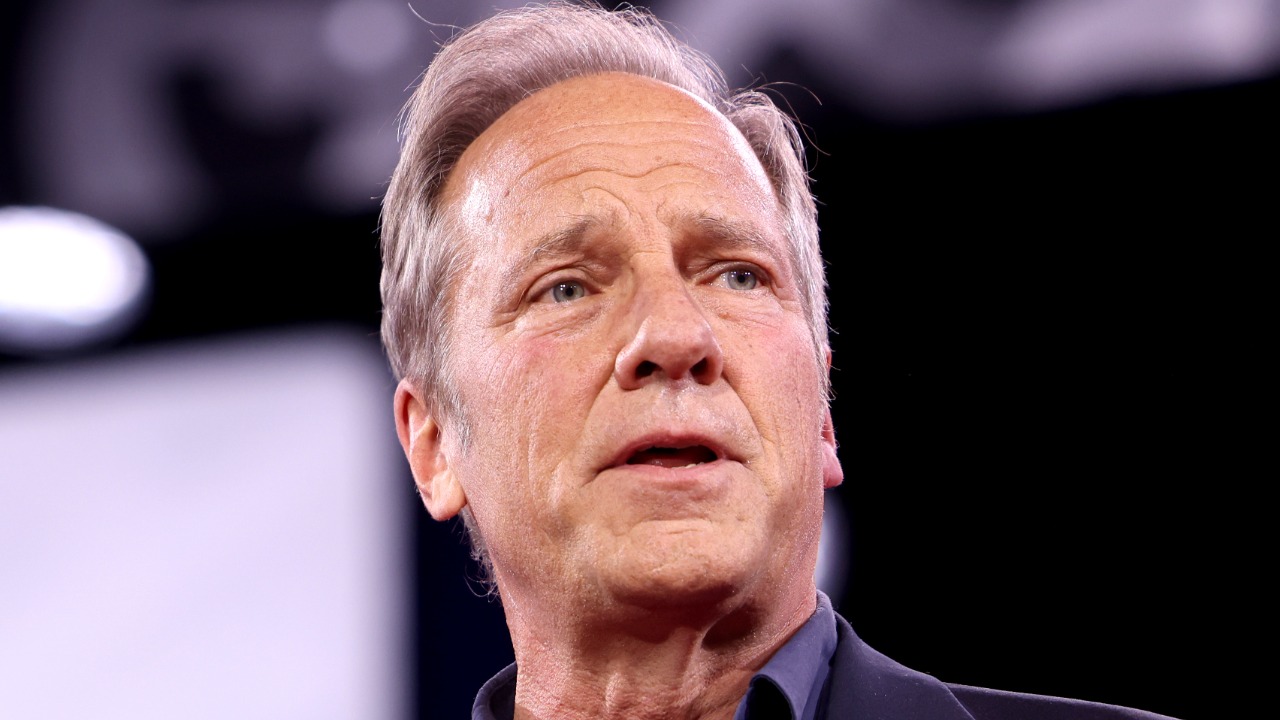

Mike Rowe: The Real Crisis Is Lack of Will to Work

The Gap Between Open Jobs and Willing Workers

Mike Rowe has spent years emphasizing that America's biggest labor issue isn't a lack of jobs, but a shortage of people willing or prepared to do them. As companies struggle to fill roles that keep the country running, his warning about a crisis in work ethic and skills has transitioned from a cable television curiosity to a mainstream economic concern. His argument is not just nostalgia; it's a hard look at how culture, policy, and education have drifted away from the kind of work that quietly powers the economy.

The core of Rowe’s claim is straightforward: there is no broad shortage of work, but rather a mismatch between available jobs and workers ready to take them. He highlights hundreds of thousands of open positions in fields like construction, manufacturing, trucking, and energy production, which remain unfilled even as people express frustration with stagnant wages and limited opportunities. This tension reflects a deeper problem in how the country values different kinds of labor and how comfortable people are with physically demanding, less glamorous roles that don’t offer remote work options.

Labor market data supports the idea that certain sectors are desperate for workers. Reports on skilled trades show persistent vacancies for electricians, welders, HVAC technicians, and heavy-equipment operators, with employers increasing pay and still struggling to hire enough qualified staff to meet demand in infrastructure and housing projects. Analysts tracking job openings in transportation and warehousing have noted similar patterns, with long-haul trucking companies facing chronic recruitment challenges despite offering signing bonuses and higher per-mile rates. These numbers give Rowe’s rhetoric a concrete foundation: the jobs exist, but the pipeline of willing and able workers is thin.

How Culture and Education Sideline "Dirty Jobs"

Rowe often traces the problem back to what students are told about success. For years, the dominant message in schools and popular culture has been that a four-year degree is the only respectable path, while blue-collar work is treated as a fallback. This hierarchy is reflected in how rarely guidance counselors steer high-performing teenagers toward apprenticeships or community college programs in welding, diesel mechanics, or industrial maintenance, even when those tracks can lead to six-figure earnings without the burden of large student loans.

Education reporting shows that public funding and prestige have flowed heavily toward traditional universities, while career and technical education programs have had to fight for resources and visibility. Studies of postsecondary enrollment document how millions of students enroll in four-year institutions, accumulate debt, and then either drop out or graduate into fields unrelated to their majors, often at salaries that do not justify the cost. At the same time, industry groups in construction and advanced manufacturing have warned of an aging workforce and too few young entrants, a pattern confirmed in surveys of contractors who say they turn down work because they cannot staff projects. That divergence between cultural messaging and labor market reality is exactly the gap Rowe is trying to highlight.

The Skills Pipeline Problem, Not Just "Kids These Days"

It is tempting to frame Rowe's argument as a simple generational critique, but the evidence points to a more structural skills pipeline problem. Employers in fields he champions are not just asking for "hard workers," they need people with specific technical competencies, safety training, and certifications. When high schools cut shop classes and local training centers close or stagnate, the on-ramp into those careers narrows, and young people lose the chance to discover whether they might actually enjoy working with their hands or operating complex machinery.

Workforce development research underscores how fragmented the training landscape has become. Reports on registered apprenticeships show that programs combining paid work with classroom instruction can deliver strong earnings and retention, yet they remain underutilized compared with traditional college pathways. Meanwhile, surveys of employers in logistics, utilities, and manufacturing describe spending significant sums on in-house training to compensate for applicants who lack basic technical and soft skills, from reading schematics to showing up reliably for early shifts. Those findings support Rowe's contention that the issue is not laziness in the abstract, but a system that has quietly dismantled many of the practical bridges into essential work.

Rowe's Push for Alternative Pathways and Personal Responsibility

Rowe has not limited himself to commentary; he has tried to build alternatives that reflect his philosophy. Through scholarship programs and partnerships with trade schools, he has promoted short, targeted training that leads directly into high-demand jobs rather than open-ended degrees. His message blends a call for personal responsibility with a pragmatic pitch: if someone is willing to relocate, learn a trade, and accept physically demanding work, there are careers that can support a family without requiring a bachelor's diploma or a corner office.

Profiles of his initiatives describe grants that help cover tuition for programs in fields like welding, commercial driving, and industrial maintenance, with recipients often required to sign a "work ethic" pledge that emphasizes showing up on time, taking responsibility for mistakes, and avoiding a sense of entitlement. Evaluations of similar trade-focused scholarships and employer-sponsored academies show strong placement rates and relatively low default rates on any associated borrowing, suggesting that tightly aligned training can reduce both financial risk and time out of the labor force. That track record lends weight to Rowe's argument that the country should invest more in practical, job-linked education and less in one-size-fits-all academic credentials.

Policy Debates: Incentives, Safety Nets, and the Dignity of Work

Rowe's framing of a "will to work" crisis inevitably intersects with policy debates over unemployment benefits, welfare programs, and minimum wage laws. He has argued that well-intentioned safety nets can sometimes dull the incentive to take tough, entry-level jobs, especially when the pay difference between benefits and work is narrow and the work itself is physically taxing. I see that concern echoed in economic analyses that examine how benefit cliffs, where a small increase in earnings triggers a large loss of assistance, can make rational workers hesitate to accept certain offers.

At the same time, social policy research complicates any simple narrative that people are choosing idleness over opportunity. Studies of labor supply responses to unemployment insurance and expanded tax credits often find modest effects on work effort, with most recipients returning to jobs as soon as they can secure stable, decent-paying positions. Analyses of low-wage sectors like food service and retail also document high turnover and burnout, driven by unpredictable schedules, limited benefits, and physically or emotionally draining conditions. Those findings suggest that if policymakers want to support the kind of work Rowe champions, they need to balance incentives to work with serious attention to job quality, safety, and long-term mobility.

Reframing What Counts as Success

Underneath Rowe's rhetoric is a cultural argument about what Americans choose to admire. For a generation raised on stories of tech founders and social media influencers, the idea that a master plumber or a lineman can build a secure, respected life has often been treated as a consolation prize rather than a first-choice ambition. I see that bias in how rarely popular entertainment portrays skilled trades as aspirational, compared with the endless stream of dramas about lawyers, doctors, and startup executives.

Surveys of public attitudes toward higher education and work show a growing skepticism about the value of expensive degrees, especially among younger adults who have watched older siblings or friends struggle with student debt. At the same time, local reporting on infrastructure projects, from broadband expansion to bridge repair, routinely highlights contractors scrambling to find enough licensed electricians, fiber technicians, and crane operators to meet deadlines. Those parallel trends hint at an opening for the kind of revaluation Rowe is calling for, where success is measured less by job title and more by the combination of income, stability, and tangible contribution to the community.

What It Would Take to Fix the "Will to Work" Problem

If Rowe is right that the real crisis lies in our collective relationship to work, the solution will not come from a single program or speech. It would require schools to treat career and technical education as a first-tier option, not a fallback, and to expose students early to the full range of careers that keep the economy functioning. It would also require employers to invest in structured training and clear advancement ladders, so that a new hire in a tough job can see a realistic path from apprentice to highly paid expert rather than a lifetime of grinding at the same wage.

Policy proposals that expand apprenticeship funding, support community college partnerships with local industry, and smooth benefit cliffs could help rebuild the pipeline into essential work without punishing those who rely on safety nets. Cultural change is harder to legislate, but it can be nudged by highlighting real examples of people who have built solid lives in trades and technical roles, and by treating those stories as success narratives rather than exceptions. In that sense, Rowe's warning about a crisis in the will to work is less a scolding than a challenge: to align what the economy needs, what schools teach, and what society celebrates so that the jobs that keep the lights on and the water running are no longer invisible, and the people who do them are no longer in such short supply.

Post a Comment for "Mike Rowe: The Real Crisis Is Lack of Will to Work"

Post a Comment